Making a custom search engine using Common Crawl web archives and Stract

Jim Pick

Welcome to the new Hex.Camp dev blog. I’ve been posting the occasional update to my BlueSky account, but I felt it was time to set up a formal blog to capture longer updates.

Building a custom search engine

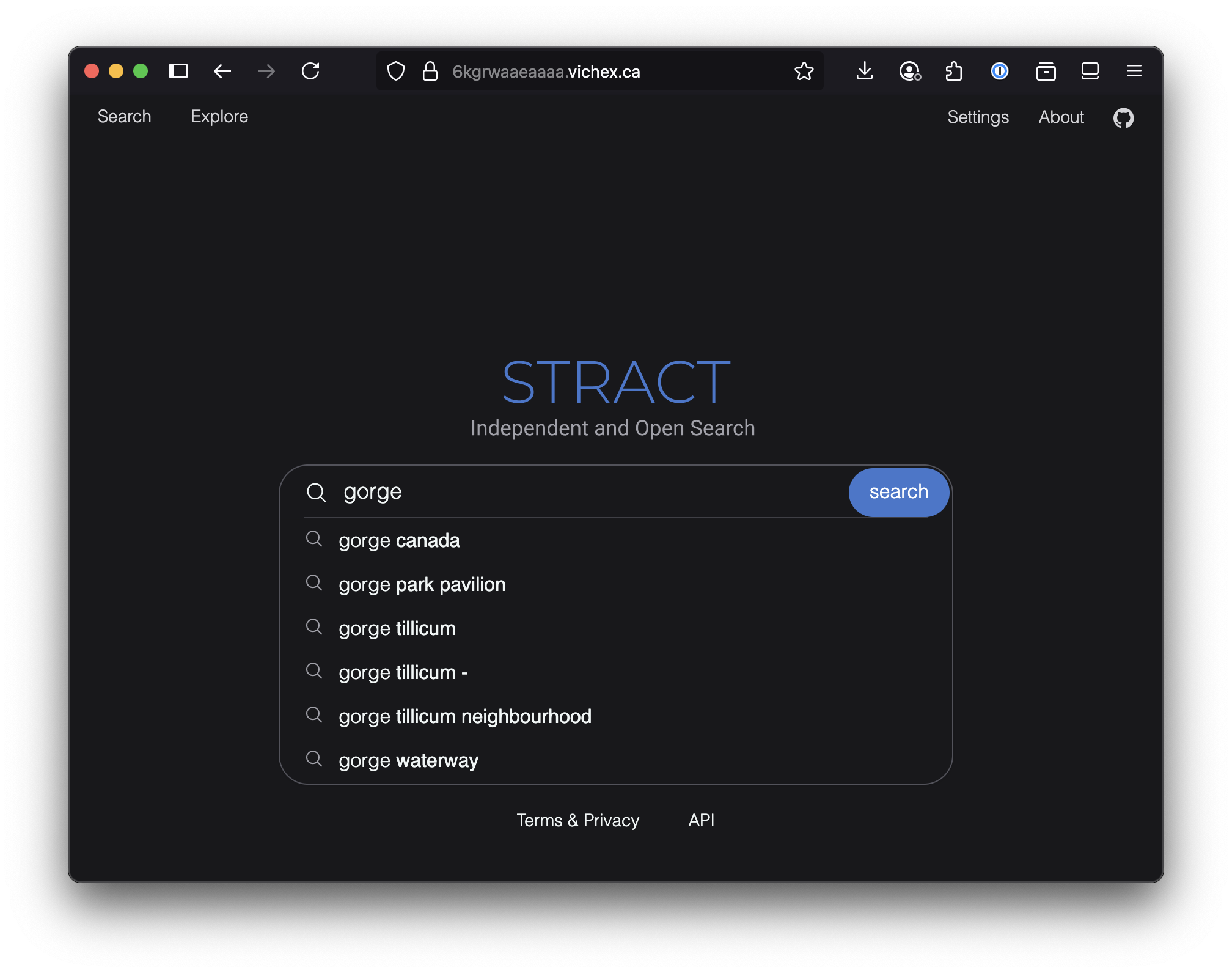

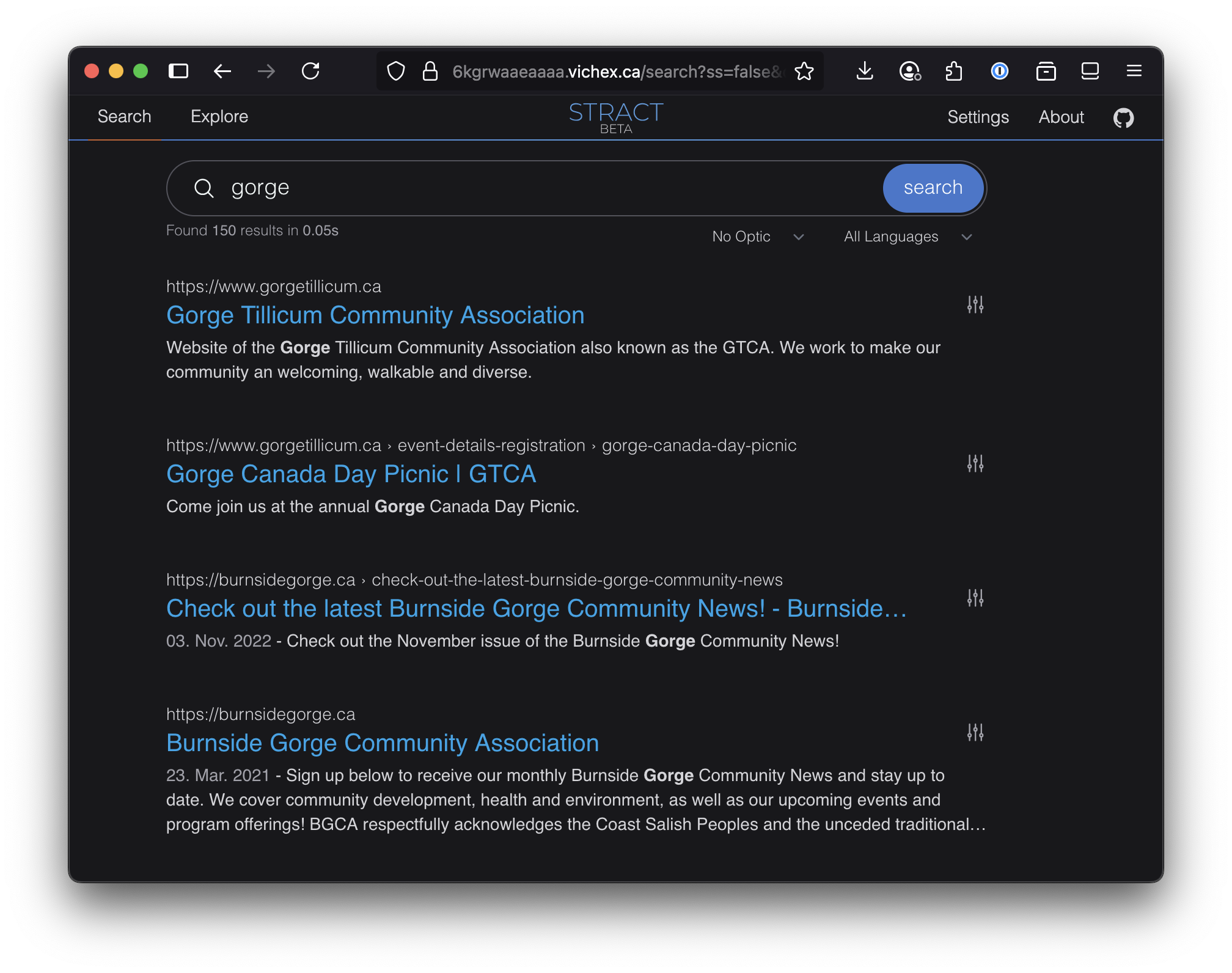

This blog post describes how I created a custom search engine that indexes the community association websites for Victoria, BC, Canada.

- Try it out here: https://6kgrwaaeaaaa.vichex.ca/

Try some sample searches: “gorge”, “festival”, “harm reduction”, “council”

Read more to find out how it was built…

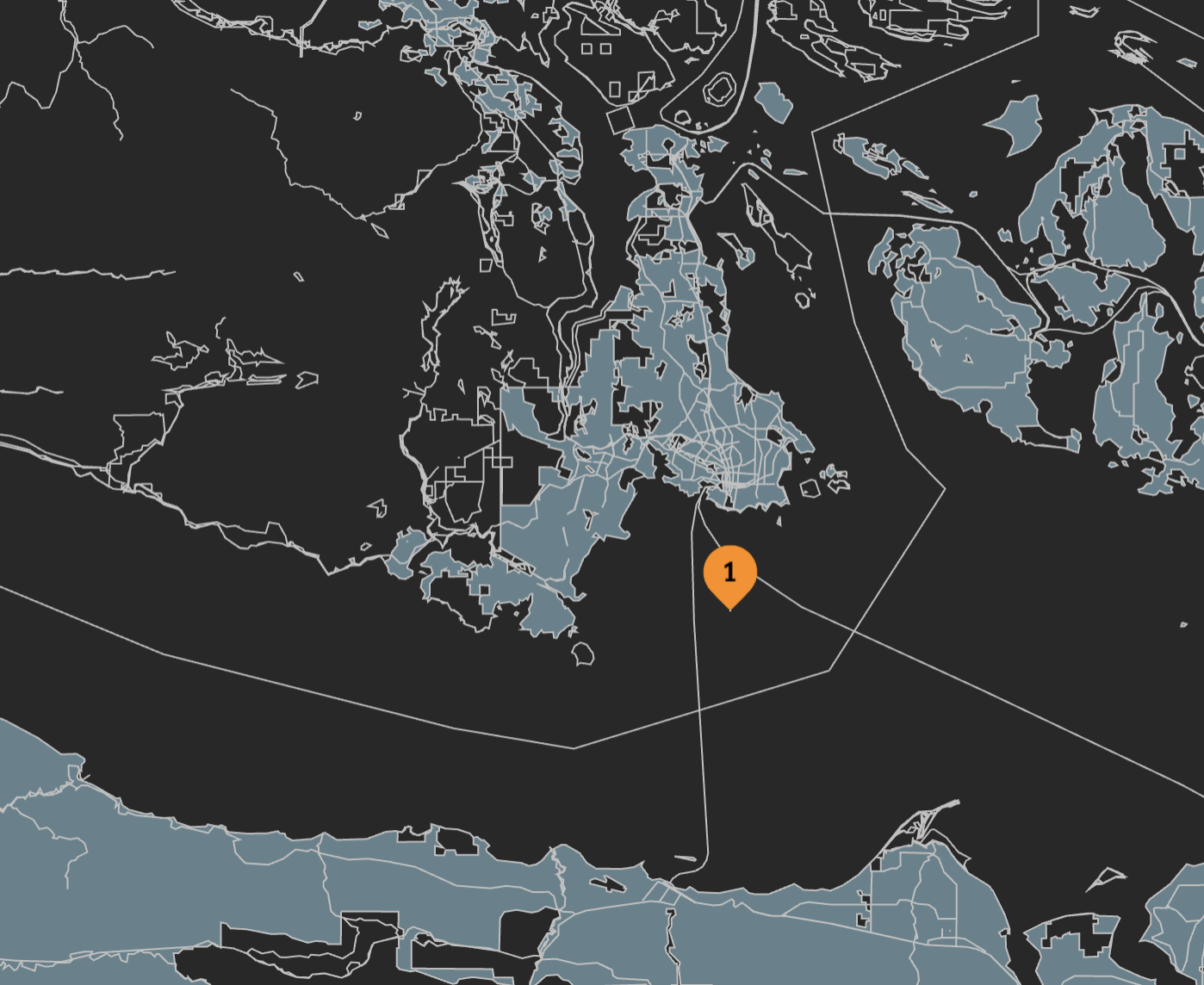

Quick primer on Hex.Camp

Hex.Camp takes the H3 geographic indexing system from Uber, and maps every hexagon cell from the grid onto a DNS address. By pairing this with IPFS, we can efficiently host millions of websites, each of which is associated with a hexagonal geographic area on the globe.

For example, this blog is published to a DNS name of 6l22glmvqj2a.vichex.ca. The 6l22glmvqj2a portion of the name is actually an encoded H3 location that exists on a map:

In this case, the location was randomly chosen to be near Victoria, BC, Canada (where I live). Unintentionally, the location appears to be in the ocean.

Hex.Camp will have many different communities, each with its own domain name. Victoria uses vichex.ca.

Although this blog doesn’t need to be associated with a physical location, by placing it on the map, it provides a hint that it should be managed together with other websites nearby.

We are using IPFS Cluster to maintain a list of all the pinned content on three IPFS servers that are inside my house. The core idea is to have different sets of content on dedicated cluster instances for each community. Eventually we will use the “Collaborative Clusters” feature to enable data mirroring within a community.

Web Archiving on Hex.Camp

Hex.Camp is designed for millions of websites, but it is still very new. Multi-user support is a work-in-progress, so it doesn’t have much original content apart from a few demos I made. Here is one example of a demo I made: Photos around Victoria

We want to discover what use cases it can excel at. One initial use case is web archiving on a community-by-community basis.

We started with WebRecorder, which is a great project from Ilya Kreymer. I’ve met him at conferences and I’ve been watching the project for years. There is a browser extension for manually capturing web archive files, plus a hosted service for scheduling crawls, and even an open source playback library that can be embedded into standalone web pages.

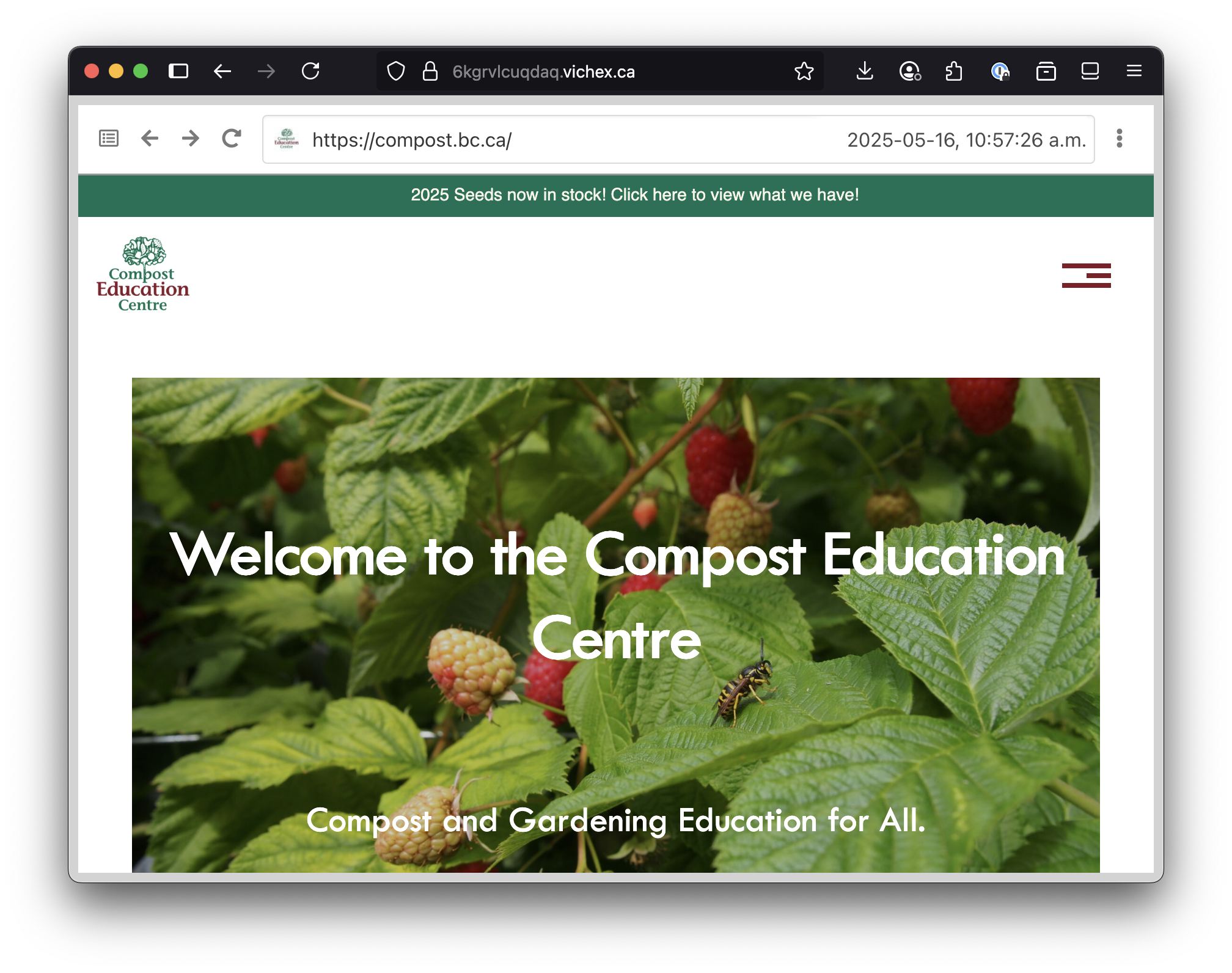

To test it out, I captured a WACZ file using BrowserTrix for the Compost Education Centre in Victoria. Because it has a physical location, I can allocate a hexagon-based website to hold the data. I used a self-hosted instance of ReplayWeb.page together with the WACZ file on IPFS to make it browseable from the web.

You can see the hosted web archive here:

Here’s what it looks like:

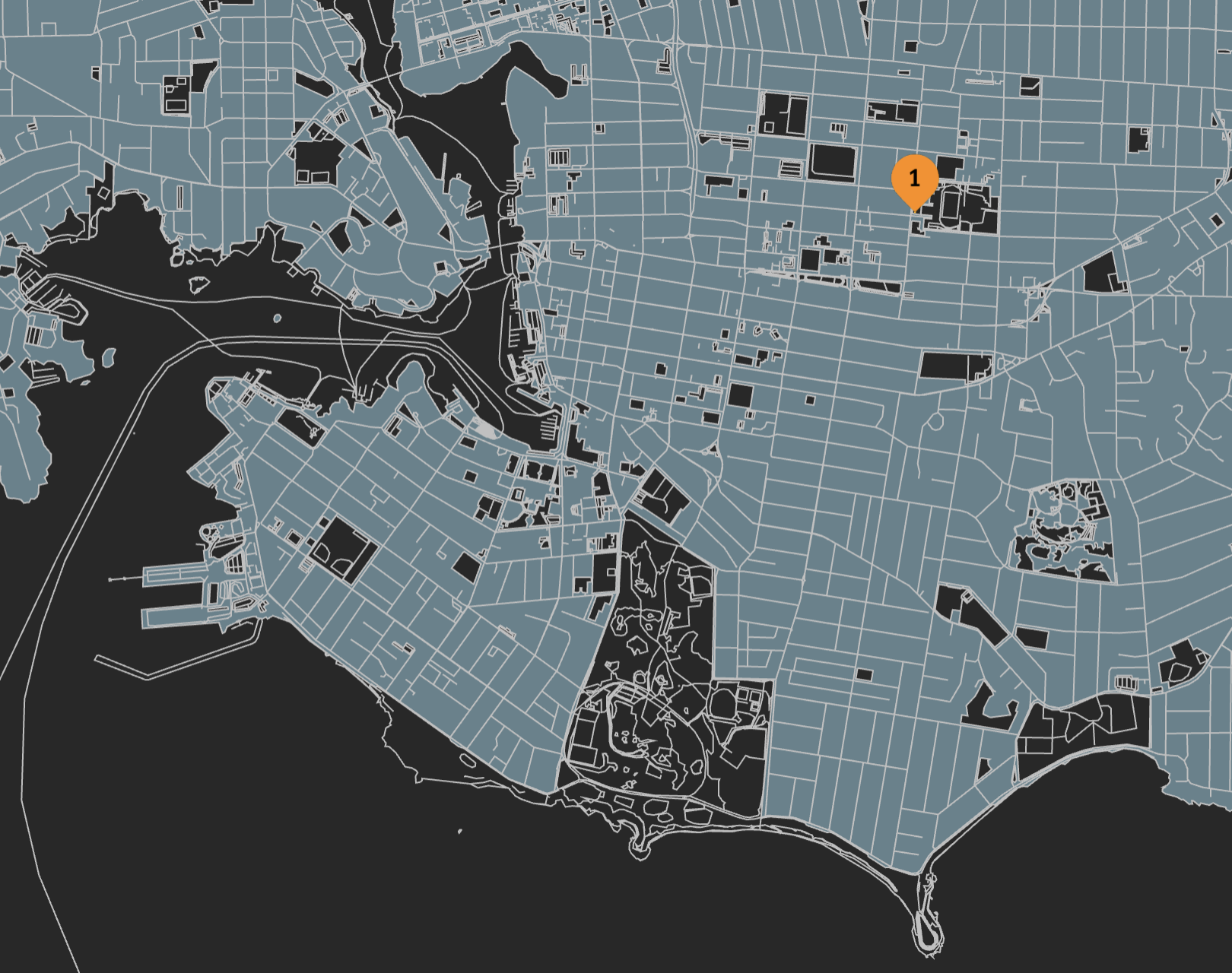

Here’s where 6kgrvlcuqdaq appears on the map. It is in the same place as the physical location of the centre:

While trying to get this to work, I discovered a small bug in IPFS which was quickly fixed. I used to work on the IPFS team, and I know everybody involved, so it was fun to actually find a bug!

Open Source Search Engines

We want to make it possible for a community to archive many of their local websites, so they could be saved and made available for posterity (if the community also has enough disk space for it). It would be like a hyperlocal Wayback Machine.

I started to wonder if it would be possible to make a search engine with the same data?

Google search is completely dominant, but they have enshittified the results with ads and AI. Now is a bad time to trust a US-based goliath with a surveillance capitalism business model. There must be open source alternatives, right?

I did some research and I came up with a short list of 4 projects that seemed active:

Seems to be the oldest project with a small community, written in Java, designed to be peer-to-peer. There’s also a more recent rewrite called YaCy Grid but there was less information about it.

A new project that has a lot of recent activity. Written in Python.

Another active project. Written in Java.

Another recent project, written in Rust. Open source development appears to have been paused since December, 2024, but they appear to have plans for the future.

I decided to try out Stract, since I’ve done a few small Rust projects lately, and the architecture docs made me think it was pretty clean. It uses the Tantivy search library, which is similar to Lucene, but written in Rust.

Web archive data from Common Crawl

Another reason I decided to try out Stract was that they originally used WARC files from the Common Crawl project. Stract has their own crawler now, but I wanted to use my own WARC files (the WACZ files from WebRecorder are just Zip files with WARC files inside).

The Common Crawl WARC files are very large, and contain thousands of websites per WARC file. Fortunately, there is a Python-based command line tool that will extract data from recent crawls for a specific URL:

For example, to extract just the pages below a certain URL, you can use the tool like this:

cdxt --crawl 1 --limit 50 --verbose warc 'secure.pickleballcanada.org/club/victoria-regional-pickleball-association/*'

That will create a WARC file with just the pages from the specified website.

The download server from Common Crawl is severely rate-limited to prevent abuse, but it seems to work for a smaller experiment such as this.

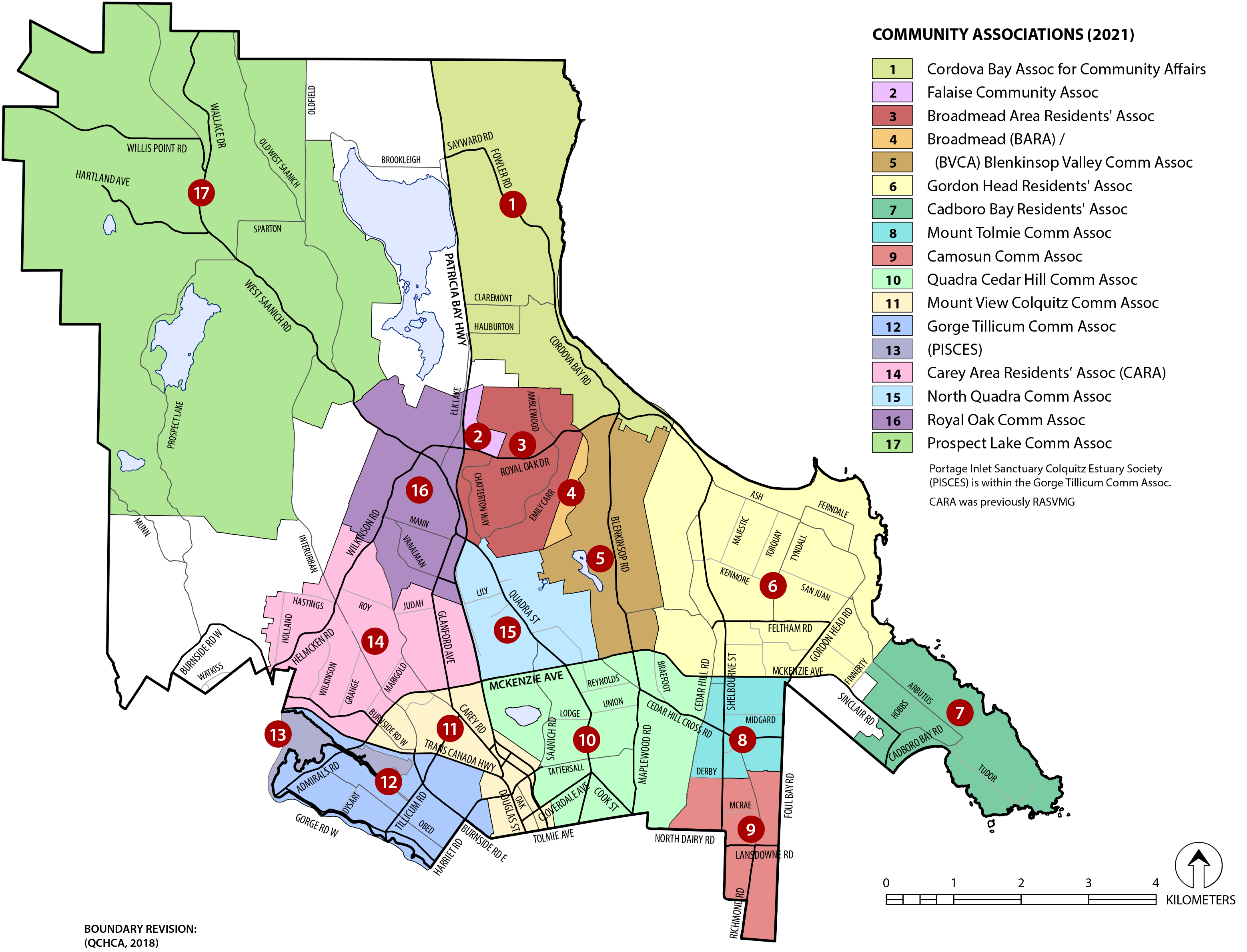

For my initial demo, I decided it would be useful to capture the latest crawl data for the community associations in Victoria and Saanich (part of Greater Victoria).

Victoria: https://www.victoria.ca/community-culture/neighbourhoods

Saanich: https://www.saanich.ca/EN/main/community/community-associations.html

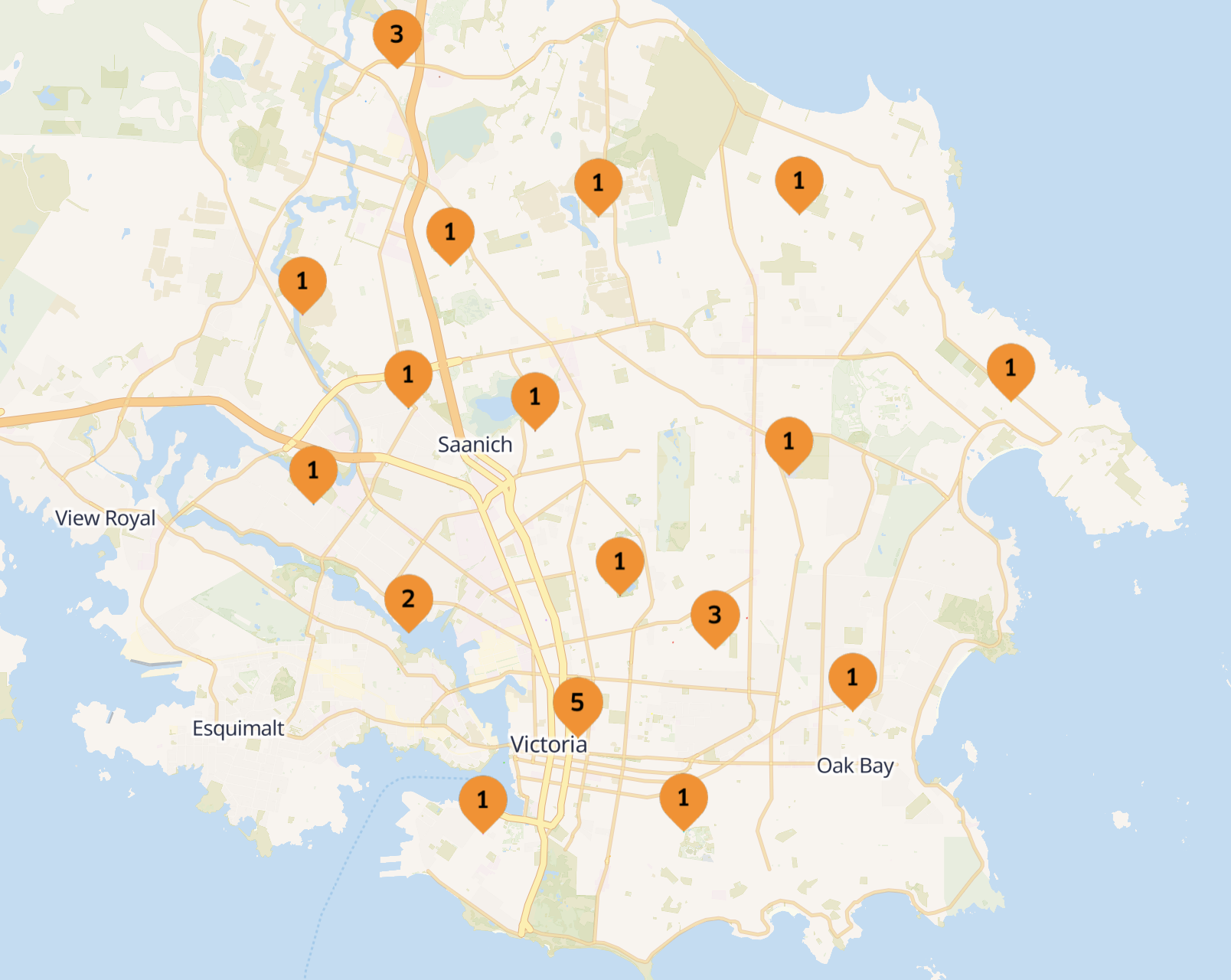

I made a crude script to capture the data for all the community associations. I then reserved 2400 hexagon cells covering all of Victoria, and allocated hexagons to store each captured web archive based on where they are located on the map. Then I uploaded the WARC files to IPFS (with the ReplayWeb.page user interface so they can be viewed).

For example, the Gorge Tillicum Community Association is archived at https://6kgrvkneaaaa.vichex.ca/

Compared to a web archive created with WebRecorder, the Common Crawl archives don’t have images, so they don’t render well with ReplayWeb.page. They do have all the text that a web search engine needs though. Also, the Common Crawl spider has to cover the entire world, so it doesn’t capture all the pages on sites that are very deep.

Another drawback with the Common Crawl data is that their crawler respects robots.txt files, so several of the community associations have no data. For example, the James Bay Neighbourhood Association has very little data: https://6kgrue2eaaaa.vichex.ca/

Just for fun, I also made a little clickable map with all the archives on it: https://6kgruaaeaaaa.vichex.ca/

I also have a web page that lists all the community associations with links to them and their associated web archives: https://6kgruqaeaaaa.vichex.ca/community-associations/

Experimenting with Stract

To get started with Stract, I started with the instructions on GitHub:

There is a Contributing.md file that documents the setup procedure.

In the discussion forum, the developer has some extra info on how to get started … how to build the indexes, etc.

The first issue I encountered was when I ran just configure … it starts by downloading

some data files from a self-hosted S3 compatible web bucket hosted by the developer. Unfortunately, the bucket with the files appears to no longer be there, so it downloads a bunch of XML error messages instead of the data.

I did some research, and I found some replacement files from the Internet that I could substitute. I got bangs.json from the test cases, english-wordnet-2022-subset.ttl from the upstream Wordnet project, sample.warc.gz from a WARC file I had created, and a test.zim file from Kiwix.

I’ve uploaded the required data files here in case anybody else needs them: https://6kgrvaaeaaaa.vichex.ca/

Once I got it built and running, I modified the configure scripts to point at my WARC files from Common Crawl, and it would build indexes, but the indexes were empty.

I dusted off some of my Rust debugging skills, and I dug into the code. It turns out that the WARC parser in Stract is somewhat strict … it is only coded to work with the WARC files that are emitted from its own web crawler code. Those files have separate entries for “request”, “response” and “metadata”, and it expects all of those entries to exist. The WARC files from Common Crawl didn’t have the expected “request” and “metadata” entries. I hacked the Rust code so that the parser is a bit more lenient and only looks for “response” entries (probably breaking it in the process for the other style of WARC file).

You can find my “hacks” here:

To build the indexes, several commands are needed. After building the binaries (cargo build), I made some simple scripts to build the indexes:

I also updated some of the config files in that branch.

To run the search backend, there are 4 different daemons to start.

just dev-search-serverjust dev-entity-search-serverjust dev-webgraphjust dev-frontend

The frontend is written using Svelte with the Node.js SvelteKit adapter. The frontend daemon can be started with just dev-frontend. The frontend/.env file can be edited to point at the backend endpoint.

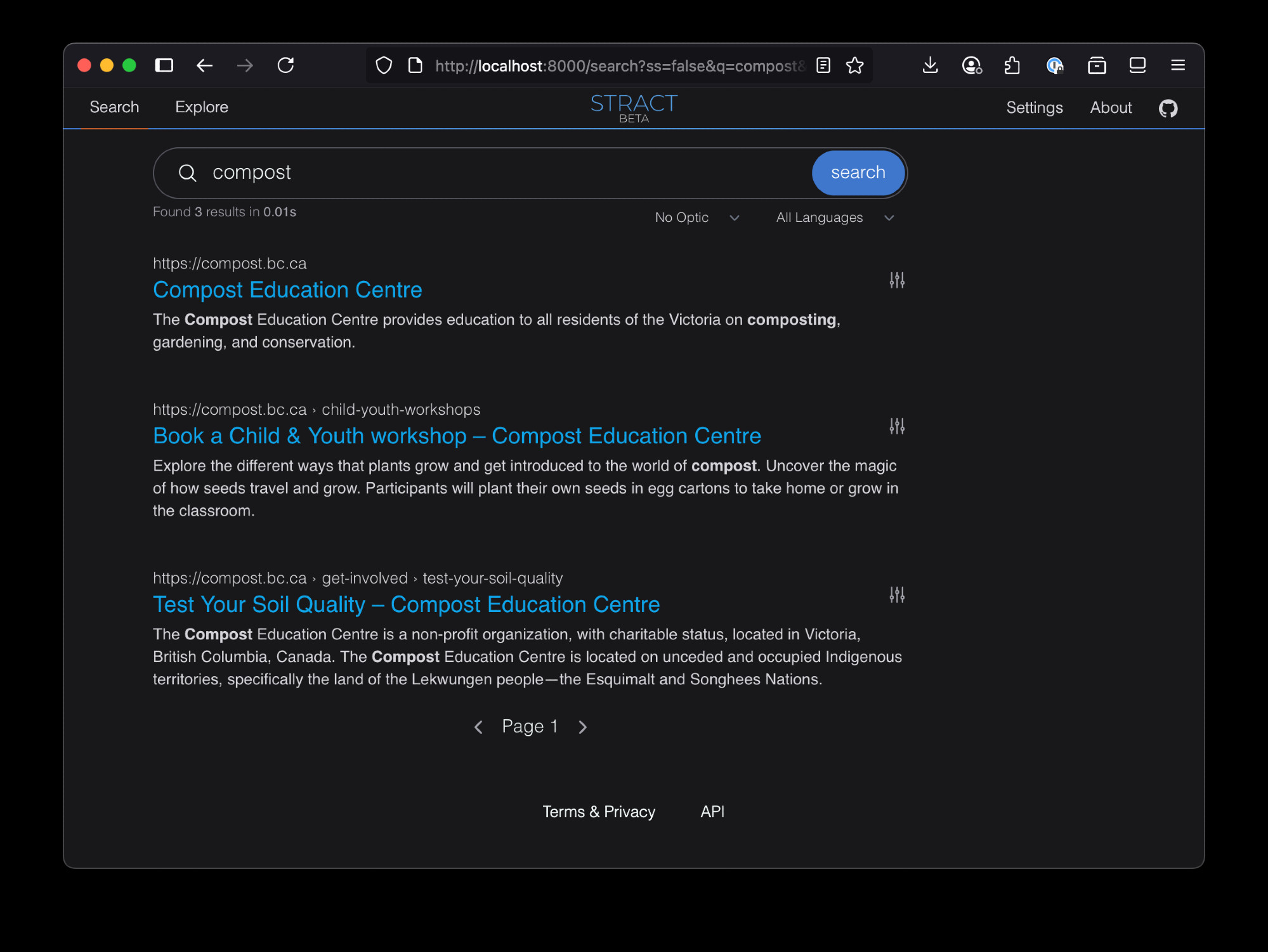

After building the indexes, starting the backend daemons and the frontend, I was able to run Stract on my laptop. Amazingly, the search worked!

Setting up Stract on Kubernetes

It was working on my laptop, so the next challenge was to get it deployed publicly.

All of the backend software for Hex.Camp runs inside my house on my “homelab”. I’ve standardized everything on Kubernetes and Knative. Everything inside the cluster is deployed using ArgoCD.

For the backend Docker image, I created a Dockerfile using cargo-chef.

To test the Docker images for the backend daemons using a local Docker instance (not Kubernetes), I made the following scripts:

The frontend Dockerfile was trickier because the frontend is a Node.js and SvelteKit app, but also has Rust parts that need to be built with wasm-pack.

For the backend, I created a Kubernetes deployment with 4 containers in a single pod for each backend daemon. It is deployed into the namespace ikgrw which is the Hex.Camp hexagon ID that covers the Victoria area. I would have preferred to deploy it as a scale-to-zero Knative service, but it builds some indexes on startup, so the cold start time is not fast enough.

I built the index data files on my laptop, and uploaded it to another hexagon-based website here: https://6kgrwqaeaaaa.vichex.ca/

I manually copied the files into the Persistent Volume for the backend. I haven’t done it yet, but I think I will try to add an Init Container to automatically download the index data via IPFS when the pod starts. When I want to update the search index data, I can push updated indexes to the Hex.Camp hexagon-based website using IPFS, and then restart the backend pod.

For the frontend, it is mostly stateless, so I was able to deploy it as a Knative service. So it will spin down to zero instances when nobody is using it. The resources are here: Kubernetes/ArgoCD resources for frontend deploy

I did try to change the frontend to use the static SvelteKit backend so I could just upload it as a static website to IPFS, but it appears to depend on some logic that gets built into the Node.js backend.

Demo Search

After all that, I now have a demo search instance online!

- Try it out here: https://6kgrwaaeaaaa.vichex.ca/

Some sample searches: “gorge”, “festival”, “harm reduction”, “council”

The Hex.Camp DNS system still needs some performance optimizations, so it might take a second or two for the site to load and the search results to appear. Occasionally it is a bit glitchy. Also, the whole system is deployed on machines inside my house.

There are a lot of things that could be done to make a production-class deployment more performant.

I made a little Search Experiment Website with documentation and links for this experiment, plus future efforts.

Next Steps

The current demo indexes 28 websites with about 700 webpages. The index files take up 60MB.

It would be interesting to try to build another index with a much larger set of sites.

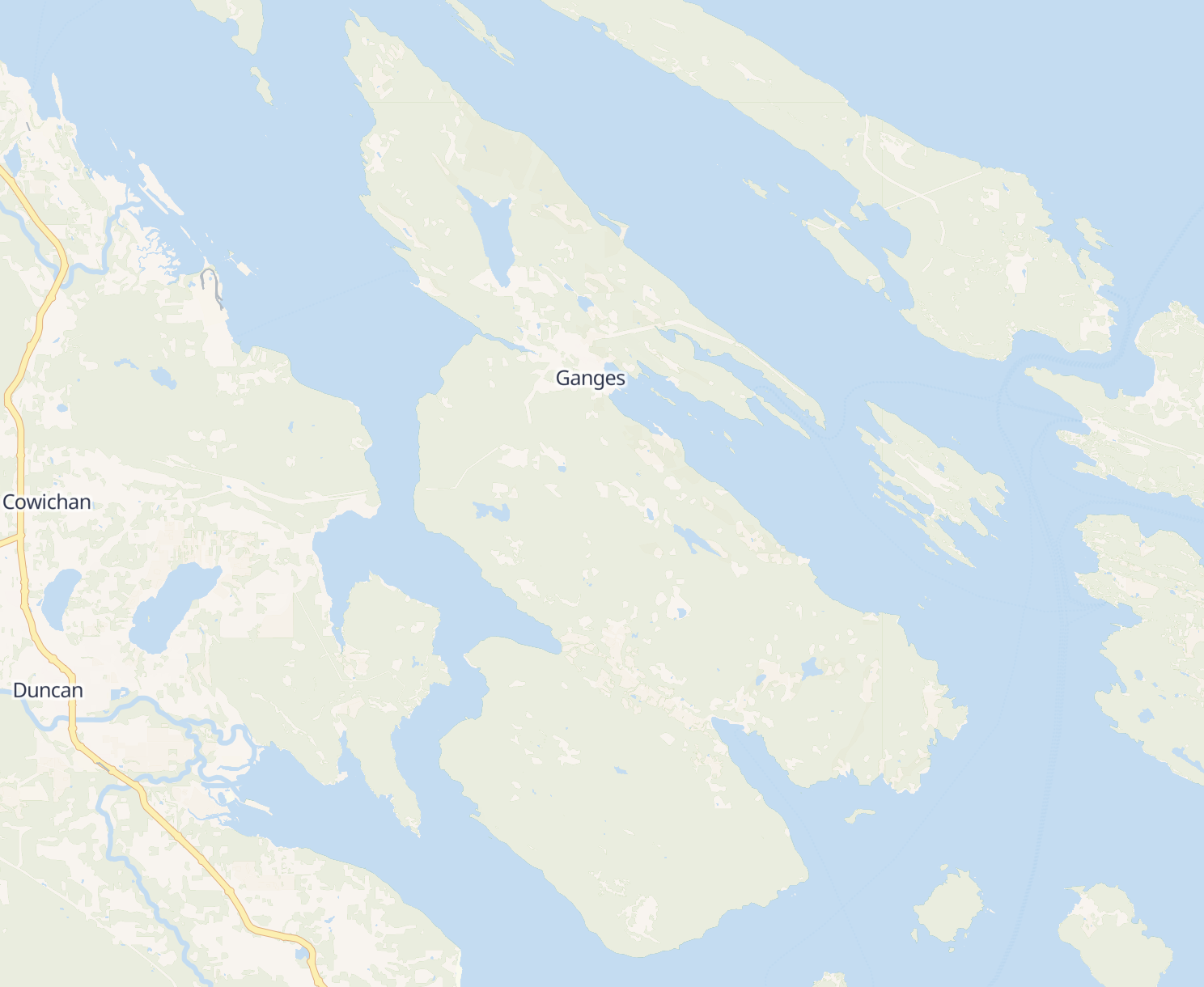

We are going to the DWeb Camp Cascadia event on Salt Spring Island on August 8-10, near Victoria.

It is a small island, so it would be interesting to see if we could collect Common Crawl data for a larger set of websites and build a search index that covers most of the websites on the island!

We have many more ideas. Wouldn’t it be interesting to make a local news search engine? Or a search engine for a particular global topic?

The front end webpages are unmodified in this demo, but it would be useful to be able to customize them, or make it embeddable in other web pages.

The search index for this demo was manually prepared on my laptop. Other parts of the Hex.Camp publishing pipeline are already event-driven using Knative Eventing and Kafka, so it would be natural to add some events and triggers to automatically update search indexes as new web archive data is added or updated.

We don’t know what is happening with the upstream Stract project, but we plan to reach out on the discussion forum to share our results.

We would also really love to collaborate with other people in the web archiving community to extend this work.

As for Hex.Camp, it is entirely self-funded at the moment. We work on it when we have time between freelance consulting work. Currently, we have availability for projects.

As Hex.Camp matures and opens up to multiple users, we do plan to put some fundraising mechanisms in place so that individual communities can be self-sustaining.

It would also be nice if we could attract some grants or other funding so we can spend more time on pushing it forward. This is a new thing for us, so any help is appreciated! At the moment, we have set up a GitHub Sponsors page.

Please reach out to our small team with your ideas or feedback! I’m always at @jimpick, either on BlueSky or via email at jim@jimpick.com. Or schedule a meeting with me at Calendly.